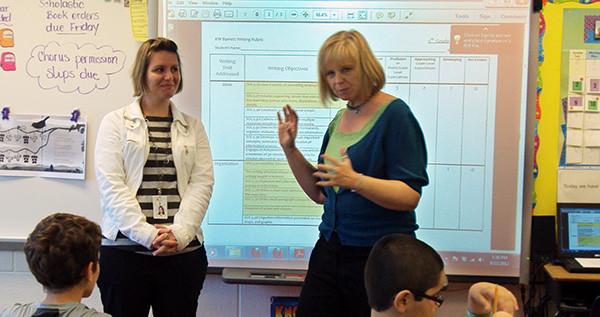

Photo courtesy of Laurie Sullivan

There often seems to be a great divide between the humanities instructor at the post-secondary level and the K-12 teaching staff. This divide is called the rubric. Based on what I’ve learned in my own education classes and from mini-courses at various Centers for Teaching and Learning, the grading rubric is a key feature of pedagogy. (If I am wrong about this, please feel free to correct me!) As one Teaching and Learning staff member explained to me, the rubric is more fair to everyone involved: to the students, because they know in advance what they will be graded on and what to expect; and to the instructors, because they have a less-biased way to evaluate student performance in notoriously squishy fields like essay writing.

This is fair, in a way; admittedly grading is difficult (and makes people cranky: see “What grades really mean”. It also ties in to last month’s “Learning Outcomes” piece: the point of the rubric is to decide what you want students to learn before they do a given task, and then grade them on how well they’ve done that. Certainly it is more sensible than making it up as you go along.

But a good essay can’t be captured by a rubric, as Bardiac argues via a comparison to basketweaving. Writing well is an art, not a mechanical skill; while a rubric can certainly be used to separate the competent writers from those who have lots to learn, it is less able to separate the exceptional from the merely pedestrian.

But rubrics are becoming more widely-used as standardized and high-stakes testing becomes more normalized. There are websites where you can download a rubric template if you are too busy to make your own. And many teachers are concerned that overuse of rubrics means that writing is not being fairly assessed — the opposite of the original goal of the rubric! (However, there are also concerns that scorers and teachers of statewide assessments don’t view the rubric in the same way or are receiving different rubric instructions, which is a different problem.)

NPR points out that even standardized testing rubrics may provide more valuable feedback than a number grade with no comments. For example, imagine a student who received a score of “excellent” in analysis and reading comprehension, but “poor” in grammar. This student would immediately know what skills to work on to improve her performance, as would her teacher. Now consider a different district that only provided numerical grades. A similar essay might receive a 75, but the student and her teachers would not know why or how to improve.

In short, there are both pros and cons to the rubric, and it is probably not going to disappear in lower grades. Its value at the post-secondary level remains debatable, however, and formative assessment by other means may be preferable.

About the Author: Jaclyn Neel is a visiting Assistant Professor in Ancient History at York University in Toronto, Ontario.